Leonardo Da Vinci's Muse

Biomimicry: the art of learning from Nature...

Human subtlety will never devise an invention more beautiful, more simple or more direct than does nature, because in her inventions nothing is lacking, and nothing is superfluous.

The natural world has always been our greatest teacher.

For millennia, humans have marveled at the spirals of seashells, the hexagons of honeycombs, and the beauty of birds in flight. Yet, few have looked at nature with as much curiosity and ingenuity as Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo was the ultimate student of the world around him. He didn’t just observe — he imitated. From the wings of birds to botanical studies, he examined, sketched, and tried to uncover the mechanisms behind nature’s designs.

Today, we call this biomimicry: the practice of learning from and emulating nature’s forms, systems, and processes to solve human problems. For a perfect example of biomimicry in action, look no further than the pages of Leonardo’s notebooks.

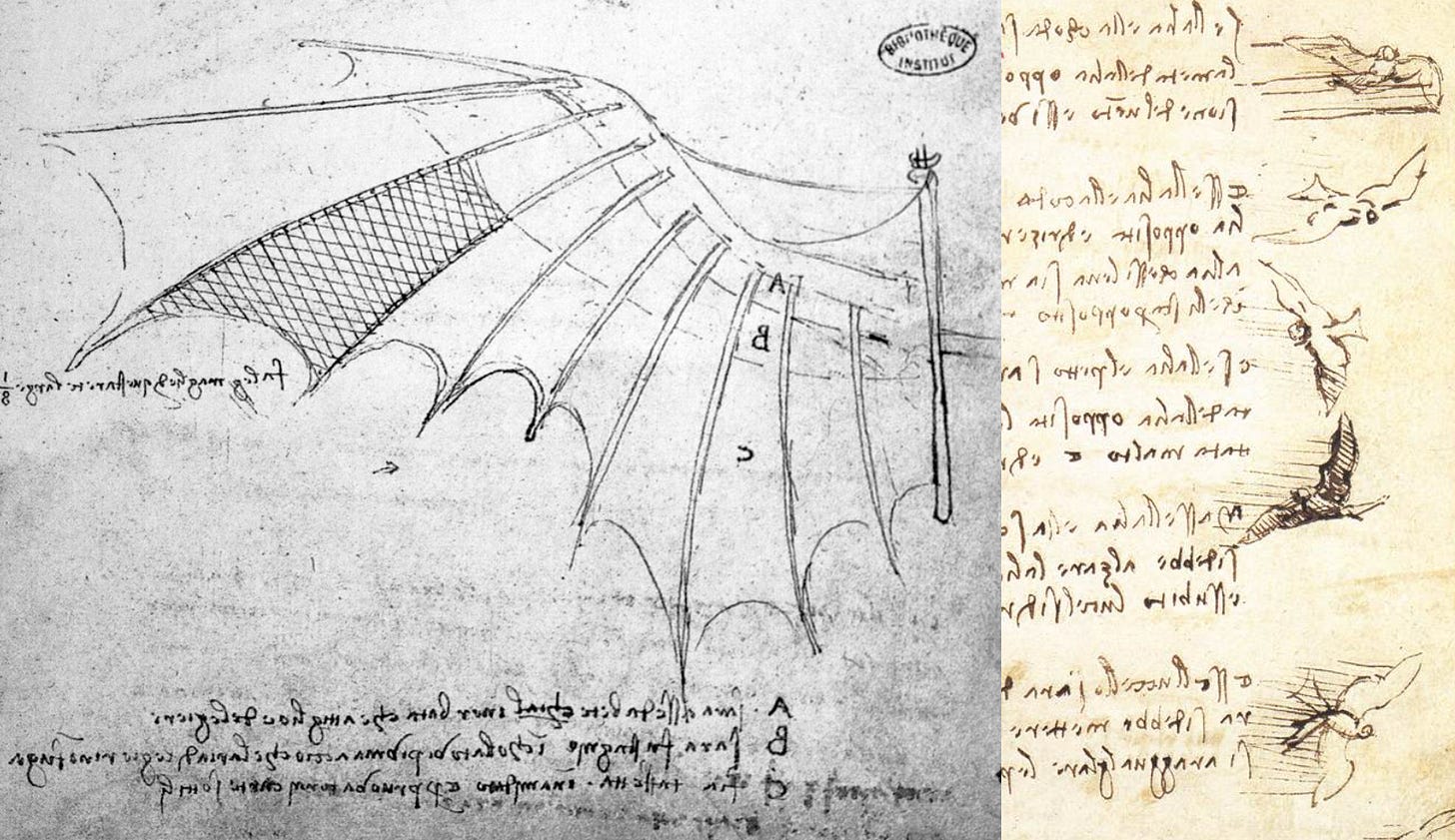

In his Codex on the Flight of Birds, he meticulously analyzed how their wings curved and moved through the air. Inspired by this, he designed machines meant to carry humans skyward. Were they perfect? Hardly. But Leonardo wasn’t concerned with perfection. He wanted to understand. In nature, he saw answers to questions no one had yet thought to ask. To quote Sigmund Freud:

He was like a man who awoke too early in the darkness, while the others were all still asleep.

Nature as the Ultimate Engineer

Leonardo wasn’t alone in his fascination with nature. The idea of learning from natural systems runs deep in history, though we often forget it. Gothic architects studied trees to design ribbed vaults. Boat builders watched fish to understand how hulls might cut through the water.

But Leonardo took this curiosity to new heights. He saw nature as not just beautiful, but functional: “There is nothing in all nature without its reason.”

The spiral of a seashell wasn’t simply decorative — it was an elegant solution for strength and growth. The veins of a leaf weren’t just pretty patterns; they were pathways for efficiency. Leonardo understood something we’re still rediscovering today: nature doesn’t waste. Nature designs for resilience, for function, and for beauty all at once.

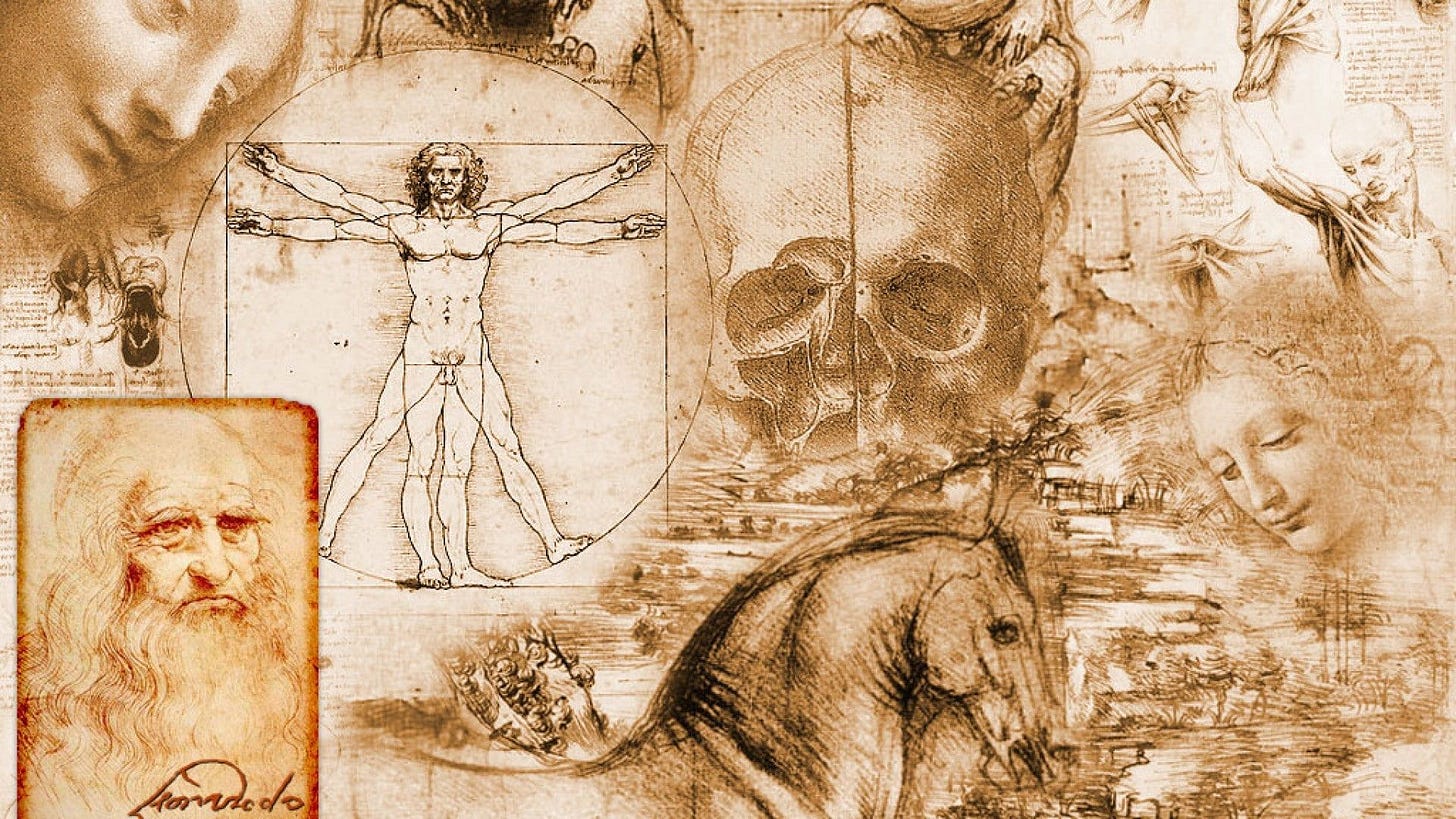

Take one of his most famous drawings, the Vitruvian Man. On its surface, it’s a study of human proportions. But underneath, it’s an exploration of symmetry, balance, and harmony — principles that exist everywhere in the natural world.

The spiral of a fern, the petals of a flower, the wings of an insect — all of these obey patterns that Leonardo recognized and revered:

Nature has her own logic, her own laws, she has no effect without cause nor invention without necessity.

Biomimicry Today

Fast forward 500 years, and Leonardo’s way of seeing the world is more relevant than ever. Engineers, architects, and designers are returning to nature for inspiration. Bullet trains are shaped like kingfisher beaks to reduce noise and drag. Skyscrapers mimic termite mounds to regulate temperature. Wind turbines copy the fins of humpback whales to move more efficiently.

Even the Eiffel Tower reflects nature’s genius… Did you know that it was designed off the femur bone? By mimicking the body's longest bone — known for its strength and lightness — the tower's designers created a unique, lightweight structure made of wrought iron, combining both durability and minimal weight.

Today, the modern biomimicry movement has a simple premise: nature has already solved most of the problems we’re trying to fix. Need to build something strong but lightweight? Look at bones. Want to reduce friction in water? Study sharkskin. Nature, with its 3.8 billion years of research and development, has solutions waiting for us.

Leonardo, of course, didn’t have the tools we have today. He couldn’t build a functioning fighting vehicle or test his aerial screw designs. But his spirit of curiosity remains a guide. Biomimicry isn’t just about copying what we see: it’s about understanding why nature works the way it does.

It’s not about the answers… it’s about asking better questions.

The Art of Asking Questions

Leonardo once wrote, “Nature is the source of all true knowledge.” He didn’t mean that we should merely admire it. He meant that we should interrogate it, take it apart with our minds, and imitate its wisdom.

Physicist Bulent Atalay said in a talk at NASA’s Langley Research Center: “No self-respecting artist goes around counting tree branches, but Leonardo did. He was a scientist doing art. It was always the patterns he was after. Proportions, patterns, the mathematics behind it.”

How does a bird take off? How does a spider’s web stay strong? How does a lotus leaf repel water? These are the kinds of questions that lead to discoveries. And they’re the kinds of questions Leonardo spent his life asking.

Biomimicry, at its core, is about humility. It’s about recognizing that nature isn’t just a backdrop for human progress; it’s a muse and a timeless teacher. The ultimate “Renaissance Man” knew that. He saw the natural world as a masterpiece and a blueprint all at once.

If Leonardo were alive today, you can bet he’d be at the forefront of biomimicry. He’d be sketching whale fins, spider webs, and butterfly wings, dreaming up machines and structures that merge art, science, and nature. And he’d remind us that the answers we’re seeking have been right in front of us all along…

Thanks for reading! I’m curious — what was your favorite example of biomimicry? I’d love to hear your thoughts and also learn what topics you’d like us to explore in future pieces as we dive deeper into the world of beauty.

I really enjoyed reading about the Tower being designed around the femur bone ..

As a child growing up ,I spent time in my Fathers Clinic where he had an x-ray screen .He was looking at lungs . I immediately saw tree's . Oxygen from tree's and lungs needing what the tree could provide us humans blew my little child mind . I never looked back . I saw Biomimicry in every thing I saw in nature ..

A few years ago I learnt about the fabric industry copying the mechanic's of butterfly wings and how they are rain repellant ..Water doesn't touch the wings for long enough to damage them due to light fractuals and vibration ..Water hovvers just above the wings and then drops away ...

And crash helmets designed using woodpecker bone structures .

The Army are incorporating textiles that can become invisible to the environment around them by mimicking animals like the chameleon .

I studies patterns in nature 30 years ago ....and now I'm studying Water . Structured internal bio water,Fourth phase water ...Our bodies are structuring devices . Our heart is like the dna sequence and the cymantics of sound spiralling ..It doesn't pump .It vortex's our blood just like rivers in nature ..

I'm an Ominist ... There is no beginning seperation between us and nature and our nature and the Omniverse ...We are all patterns .All fractuals spiralling through non linear time which is also spiralling ...The infinite Beauty of Patterns in All Life .

🌀🌀🌀🌀🌀🌀🌀🌀

Leonardo created a spiral staircase in marble that absolutely mimics a nautilus shell. I would love to climb those stairs. In his sketchbooks he records his curiosity and his conclusions. I don’t believe Leonardo saw himself as a part from nature, but as a part of nature; fascinated by what he saw and applying what he’d observed to solve other kinds of problems: rendering three dimensional objects on a two dimensional plane; catching the likeness of an individual by studying how it differed from the theoretical perfect. If he were to be born today, he’d still be ahead of his time.