Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty

The ancient Greek urn that inspired one of the greatest poems of all time...

There is a man standing silently in a museum, staring at a Greek urn.

From this ancient relic, the voice of the past emerges, whispering insights that would ignite the imagination of one of the greatest English Romantic poets of all time: John Keats.

Here, in the British Museum in London, the urn that inspired his most famous poem becomes both a tangible artifact and a product of his creativity. Let me explain…

A Fusion of Art

Scholars believe that the vase described in Ode on a Grecian Urn (1819) isn’t based on one specific object.

Instead, it’s a blend of several Greek works that Keats admired during his months of wandering through the museum’s halls and examining an array of prints. In particular, he was inspired by the Townley Vase and the Sosibios Vase, the latter of which he notably traced an engraving of after seeing it in Henry Moses's A Collection of Antique Vases:

Keats was a frequent visitor to the British Museum, familiar with its collection to the point where he could easily spot new additions. Ernest de Sélincourt once described the young poet with these words:

"Nothing escaped him. The hum of a bee, the sight of a flower, the splendor of the sun seemed to make his very life waver: his eye lit up, his cheeks colored, his lips trembled."

It was this profound love for classical art, combined with his inquisitive nature and vivid imagination, that allowed Keats to create one of the greatest odes in the English language — a celebration of art’s timeless beauty in stark contrast to the fleeting nature of existence.

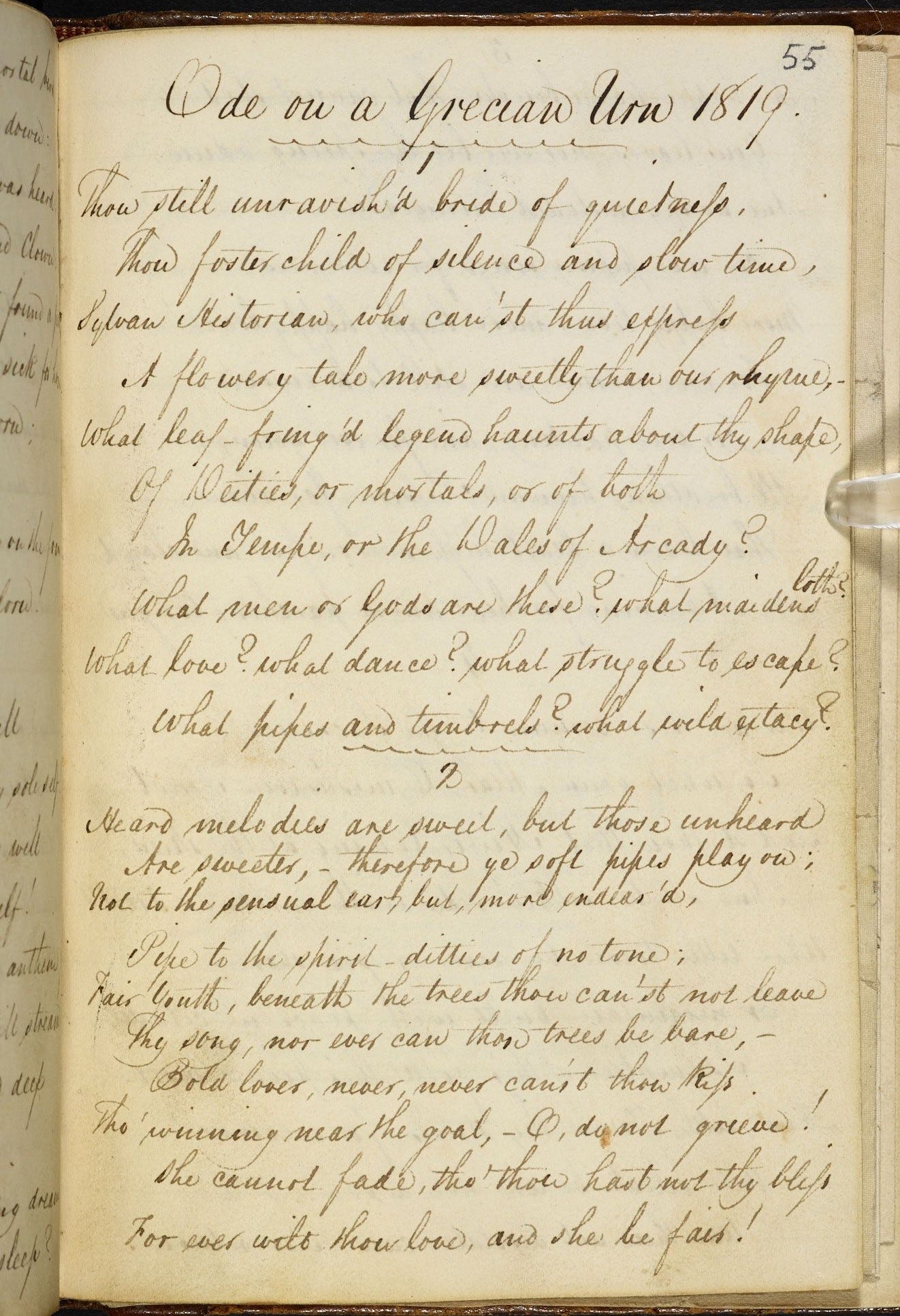

The Poem

The ode opens with the narrator calling the urn a "bride of quietness," allowing him to interpret it through his own lens. He writes:

"Thou still unravish'd bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time,"

Crafted from stone by an artist who communicates without words, the urn transcends time and tells a story through its beauty.

For Keats, the urn is more than a work of art. It becomes a portal where time is suspended, and emotions are crystallized into eternal perfection. The figures carved on its surface become keepers of secrets and desires, transcending time and space and immortalizing the defining moments of human life.

In the famous lines, "Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter," Keats then reflects on the mysterious musicians etched into the marble of the urn, reminding us that the power of our imagination often surpasses reality.

Imagined melodies resonate deeper than those we physically hear, often falling short of our expectations.

The scene depicted in the ode is eternally still because those who achieve immortality through art remain untouched by the relentless march of time.

As the years erase the world of ancient Greece, the world of Keats, and eventually our own lives, the figures carved on the urn remain. They "live" long after we are gone.

In other words, "Beauty perishes in life, but is immortal in art."

The True Meaning of 'Beauty is Truth'

Keats concludes the fifth and final stanza with some of the most famous verses ever written:

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

These lines, sparking nearly a century of critical debate, encapsulate his vision, suggesting that beauty and truth are profoundly intertwined.

The urn itself seems to speak here, as indicated by the use of quotation marks when the voice of the speaker shifts.

One interpretation sees the urn as a figure of wisdom, allowing Keats to convey a powerful message: beauty leads us to truth, and truth, in turn, is inherently beautiful.

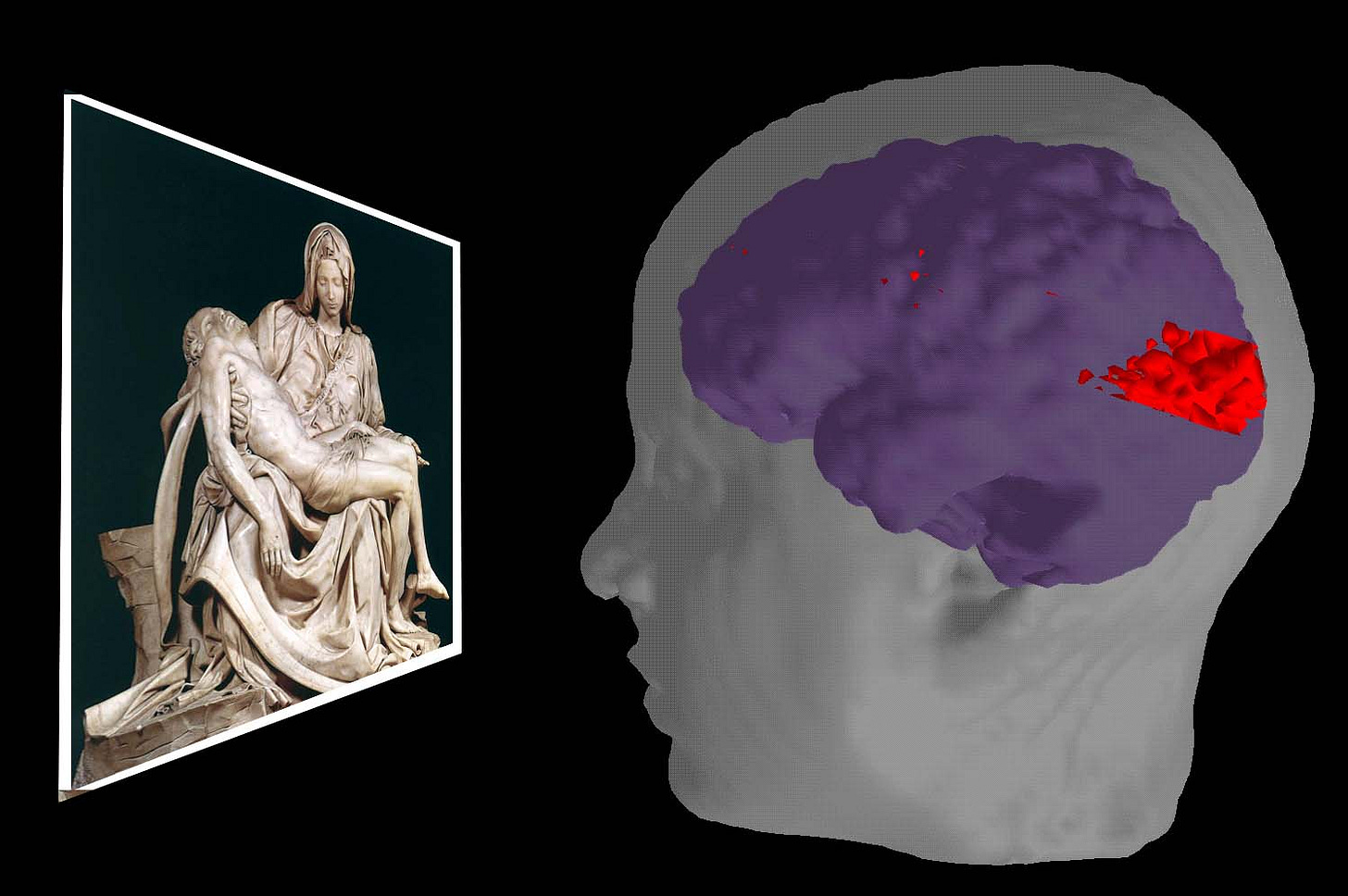

This perspective becomes even more intriguing in light of recent scientific findings indicating that beauty evokes uniform neurological responses across individuals. Encountering breathtaking visuals stimulates the release of oxytocin, leading to reduced heart rates and lower blood pressure. This physiological response transcends personal taste, implying that true beauty objectively influences everyone, regardless of their individual conditioning.

Then there’s the fact that the poem seems to suggest that a lifeless vase can summarize in five words all that humanity needs to know on Earth…

Ancient philosophers recognized three fundamental properties of being—truth, goodness, and beauty—collectively known as the "transcendentals." These principles add a spiritual layer to life, helping us connect our finite understanding with the eternal.

So, what does this have to do with Keats?

In his ode, the words "on earth" allude to the possibility of discovering truths that extend beyond the mortal plane, hinting at a higher dimension where greater wisdom resides. Although crafted by human hands, the Grecian urn offers a glimpse into the divine while simultaneously keeping its mysteries hidden.

In today’s world, defined by political polarization, relentless propaganda, and social fragmentation, one might argue that beauty emerges as our most undeniable truth, as suggested by the Platonic ideal of kaloskagathos, which asserts that all beautiful things (kalòs) are inherently true and good (agathòs). Ultimately, the most exquisite expressions of life—art, poetry, nature—bring us closer to this profound understanding.

And perhaps, there is no pursuit more inherently beautiful than the quest for truth itself.

Ode on a Grecian Urn (May 1819)

Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of Silence and slow Time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fring’d legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone:

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal—yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed

Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu;

And, happy melodist, unwearied,

For ever piping songs for ever new;

More happy love! more happy, happy love!

For ever warm and still to be enjoy’d,

For ever panting, and for ever young;

All breathing human passion far above,

That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy’d,

A burning forehead, and a parching tongue.

Who are these coming to the sacrifice?

To what green altar, O mysterious priest,

Lead’st thou that heifer lowing at the skies,

And all her silken flanks with garlands drest?

What little town by river or sea shore,

Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel,

Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn?

And, little town, thy streets for evermore

Will silent be; and not a soul to tell

Why thou art desolate, can e’er return.

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede

Of marble men and maidens overwrought,

With forest branches and the trodden weed;

Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity: Cold pastoral!

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st,

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty”—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

John Keats

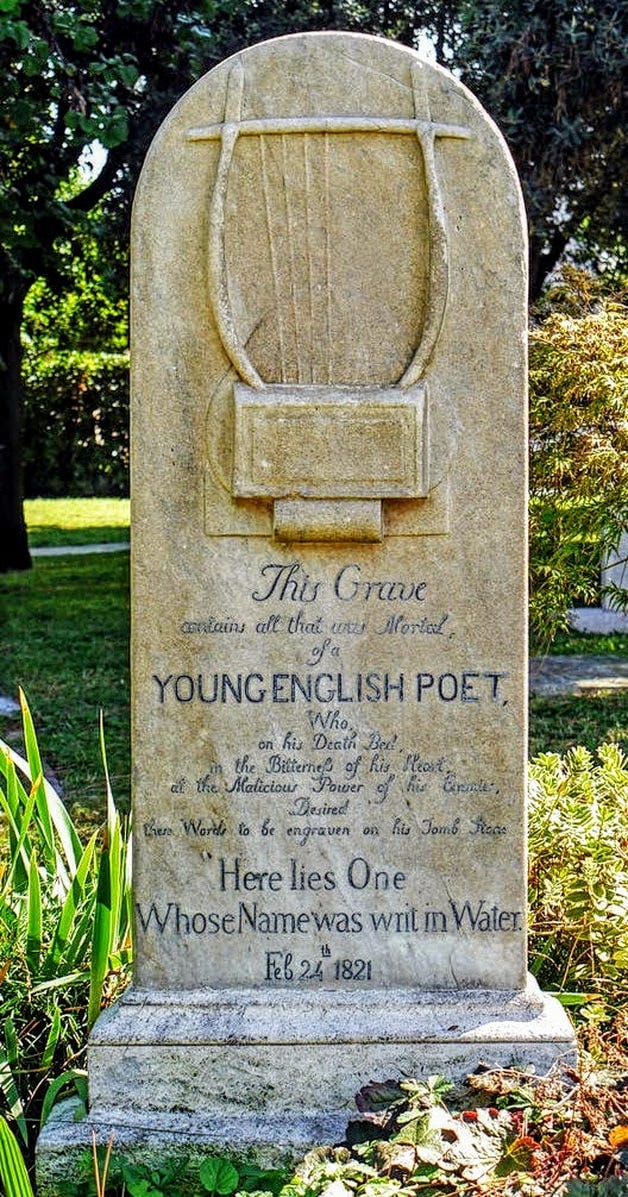

John Keats passed away from tuberculosis on February 23, 1821, at the tender age of twenty-five, and was laid to rest in Rome’s Non-Catholic Cemetery.

The poet requested that his tombstone bear neither his name nor the date of his death; instead, he chose the following epitaph:

This grave contains all that was mortal, of a young English poet, who, on his death bed, in the bitterness of his heart, at the malicious power of his enemies, desired these words to be engraven on his tomb stone “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water”

Love the connections your building upon here! Thanks for sharing. Where did you learn the art of seeing the connective tissue across these concepts?

Beautifully moving, thank you x